Lyrics from “A voz do morro” by Zé Kéti (1955)

–

I’m samba, the voice from the morro, that’s me indeed, yes sir

I want to show the world that I have worth

I’m the king of the terreiro, I’m samba

I’m native from here, from Rio de Janeiro

I’m the one who brings joy to millions of Brazilian hearts

Salve samba, we want samba

Who’s asking for it is the voice of the people of a country

Salve samba, we want samba, that melody of a happy Brazil

–

Lyrics from “Acender as velas” by Zé Kéti (1965)

–

Lighting candles has become our profession

When there’s no samba, there’s disillusion

It’s another heart that stops beating, an angel goes to heaven

God forgive me, but I’m going to say it, the doctor arrived too late

Because up on the morro, there’s no automobile to go up

No telephone to call, and no beauty to be seen

And we die without wanting to die

— Interpretation —

“A voz do morro” was the samba that brought fame to Zé Kéti in 1955, when it rolled as the theme song on Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s film Rio, 40 Graus. (Along with contributing to the soundtrack, Kéti worked as second camera assistant for the film and played a small part as the character Neguinho.) On its own, “A voz do morro” seems like an everyday samba-exaltação, celebrating the nation and the genre; the lyrics alone don’t betray protest or even melancholy. But set against the backdrop of Santos’s film, which follows the lives of five boys from the favela selling peanuts in rich areas of Rio de Janeiro on a scorching summer day, the song is deeply poignant and political. The movie contrasts the lives of these boys with the lives of their rich white neighbors in Copacabana and with the luxuriant natural beauty of the city itself. When it was released, it laid bare in a queasy fashion the class conflict and exploitation of Afro-Brazilian favelados that ran deep in Rio de Janeiro, but that the government, media, and city by and large turned a blind eye to. The movie was styled in the postwar Italian neorealist model of political dramas that mimic documentaries, and marked the start of Cinema Novo in Brazil.

Ten years later, Kéti’s low-spirited samba “Acender as velas” brought the same themes to light, but this time more acutely. Kéti wrote the song for Ronaldo Bôscoli, who was doing a vignette on his TV show about the hopeless situation of a sick boy in a favela. The samba was released in the wake of the 1964 coup that installed a military dictatorship in Brazil. The military government quickly embarked on a series of harsh and misguided policies for dealing with Rio’s favelas, and Kéti’s sambas responded to this treatment.

Zé Kéti — whose full name was José Flores de Jesús — was born in Inhaúma, Rio de Janeiro, on September 16, 1921. His nickname Kéti is an adaptation of “quietinho” – or well-behaved. He explained his name saying “quietinho” became “quieti,” which he changed to Kéti because “K was in fashion at the time — Khrushchev, Kennedy, Kubitschek.”

Kéti grew up at his grandfather’s house in Bangu until 1928, when he and his mother moved to Dona Clara, a section of the north-zone neighborhood Madureira, the samba bastion that’s home to the samba schools Portela and Império Serrano. In this 1973 documentary, Kéti recounts that his grandfather was a piano and flute player who was friends with Pixinguinha and Cândido das Neves. Kéti’s father was also a composer, guitar and cavaquinho player, and Kéti attributes his fascination with music from a young age to their influence. Kéti’s father died when Kéti was still a young boy, apparently poisoned by an ex-lover. (The samba “Meu pai morreu” is about this story; Keti said his father went crazy and died on Rio’s Praia Vermelha.) Kéti’s mother, a fabric factory worker and domestic servant, brought him along on her nights out at samba bars, and Kéti said he would always sit near the music – entranced – rather than playing with the other kids. Eventually his mother granted his pleas for a flute, and he started making music.

As a young man Kéti began frequenting the Portela samba school and composing. When he was 24, the group Vocalistas Tropicais released his composition “Tio Sam no samba,” marking his first samba to be recorded. Shortly after, Ciro Monteiro – Kéti’s inspiration in the art of playing percussion on a matchbox – recorded Kéti’s samba “Vivo bem.” But again, fame only came years later, in the mid-1950s: Nelson Pereira dos Santos was looking for a sambista for the soundtrack for Rio, 40 Graus, and actor Artur Vargas Junior brought Zé Kéti in to sing for him. Santos was enchanted – so much so that, as relates in this program, his next film with a similar theme, Rio, Zona Norte, was a tribute to Zé Kéti, who was represented by Grande Otelo‘s character.

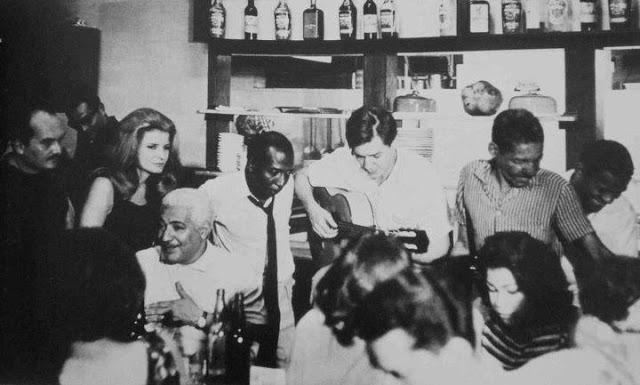

In 1963, Cartola and his wife Zica opened their legendary restaurant Zicartola and appointed Zé Kéti as artistic director of the house. Kéti was largely responsible for launching the careers of samba greats including Paulinho da Viola, who went into Zicartola in 1964 as the unknown Paulo Cesar and quickly rose to fame under his new artistic name. In the same 1973 documentary, Kéti says Paulinho’s nickname was, “modesty aside, given by his friend Zé Kéti,” inspired by Império Serrano’s Mano Décio da Viola. Kéti’s friend, journalist Sérgio Cabral, hastily used the nickname in his newspaper column and it thus became official.

During his time at Zicartola, Zé Kéti became friends with Carlos Lyra, and the two made a deal: Kéti would take Lyra to samba schools in the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro if Lyra introduced Kéti in the bossa-nova-dominated Zona Sul. That’s how Zé Kéti ended up playing a pivotal role in popularizing samba from Rio’s morros among the city’s elite, and throughout the country and the world.

In 1964, Carlos Lyra introduced Kéti to Nara Leão, the “muse of bossa nova” who was increasingly fed up with that genre. In light of the country’s political plight, Nara deemed bossa nova nauseatingly apolitical: “[Bossa nova] always has the same theme: love-flower-sea-love-flower-sea, and it goes on ad infinitum.” In a controversial interview with the magazine Fatos e Fotos, she continued, “I want pure samba, which has much more to say for itself, which is the people’s way of expressing themselves, and not something written by a small group for another small group.” Kéti showed Nara his samba “Diz que fui por aí,” which she recorded on her first LP, Nara, that same year. In late 1964 Nara released a second album, Opinião da Nara, with “Acender as velas” and Kéti’s equally political samba “Opinião.” The latter protested the military government’s policy of removing favelas around Rio’s Zona Sul and relocating residents to distant developments with names like Vila Kennedy, in honor of the government that was financing the ill-advised initiative. The refrain for that song says, “They can take me prisoner/They can beat me/They can even make me go without food/But I won’t change my opinion/I won’t leave the morro.”

Also in late 1964, the Teatro Arena opened up in Copacabana and Zé Kéti was invited to act alongside Nara Leão and João do Vale in a musical play named after his samba “Opinião.” The show addressed social strife in Rio through the three characters: João do Vale played a northeastern migrant, Kéti played the part of the malandro carioca, and Nara played the rich student from the Zona Sul. They toured the country with the tremendously popular play; the theater ended up taking on the name Opinião, and when Nara Leão took time off to rest her voice, she recommended Maria Bethânia as her replacement, and another star was revealed.

Among Kéti’s other major hits is the Carnival march “Mascara Negra” (1967, with Hildebrando Pereira Matos), which won first place in the 1967 Carnival contest and remains one of Brazil’s most beloved Carnival themes. Kéti was soft spoken, humble, and good humored, a devoted member of the Portela samba school and fan of the Vasco da Gama football club. He died on November 14, 1999, a year after receiving the prestigious Shell Prize for MPB, and a few months after the death of his close friend Carlos Cachaça, which had left him deeply distraught. He was buried in Inhaúma, with the blue-and-white Portela flag, as “Voz do morro” played in the background.

A few notes on the translations: morro means hill or hillside, but here and in general refers to the community on the hillside – the favela; terreiro was the space where Afro-Brazilian religions were practiced and where samba was created and performed; and the line “we die without wanting to die” could also be translated as “the people die without wanting to die,” since the Portuguese line says a gente, which can mean both “we” or “the people.” Since a gente is almost exclusively used in Rio to mean “we,” that’s how I translated it in the song.

–

Lyrics in Portuguese: “A voz do morro”

Eu sou o samba

A voz do morro sou eu mesmo sim senhor

Quero mostrar ao mundo que tenho valor

Eu sou o rei do terreiro

Eu sou o samba

Sou natural daqui do Rio de Janeiro

Sou eu quem levo a alegria

Para milhões de corações brasileiros

Salve o samba, queremos samba

Quem está pedindo é a voz do povo de um país

Salve o samba, queremos samba

Essa melodia de um Brasil feliz

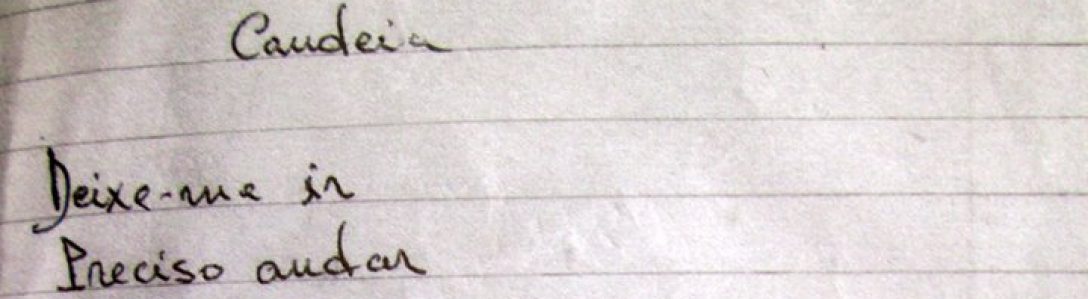

Lyrics in Portuguese: “Acender as velas”

Acender as velas

Já é profissão

Quando não tem samba

Tem desilusão

É mais um coração

Que deixa de bater

Um anjo vai pro céu

Deus me perdoe

Mas vou dizer

O doutor chegou tarde demais

Porque no morro

Não tem automóvel pra subir

Não tem telefone pra chamar

E não tem beleza pra se ver

E a gente morre sem querer morrer

Main sources for this post: Hello, Hello Brazil: Popular Music in the Making of Modern Brazil by Bryan McCann; Bossa Nova: The Story of the Brazilian Music that Seduced the World by Ruy Castro; and A Canção no Tempo: 85 Anos de Músicas Brasileiras, vol. 1 &2, by Jairo Severiano and Zuza Homem de Mello.

Thank you, I’m moved