Lyrics from “Matita Perê” by Antônio Carlos Jobim and Paulo César Pinheiro (1973)

___

No jardim das rosas / In the garden of roses

De sonho e medo / Of dream and dread

Pelos canteiros de espinhos e flores / Through the beds of thorns and flowers

Lá, quero ver você / There, I want to see you

Olerê, Olará, você me pegar / Olerê, Olarâ, you catch me

Madrugada fria de estranho sonho / [In the] Cold dead of night from a disquieting dream

Acordou João, cachorro latia / João awoke, a dog was barking

João abriu a porta / João opened the door

O sonho existia / The dream was real

Que João fugisse / That João might run

Que João partisse / That João might leave

Que João sumisse do mundo / That João might vanish

De nem Deus achar, Lerê / So even God couldn’t find him, lerê

Manhã noiteira de força-viagem / Nightish dawn of journey-force*

Leva em dianteira um dia de vantagem / [He] Has a lead a day’s advantage

Folha de palmeira apaga a passagem /A palm leaf erases his trail

O chão, na palma da mão, o chão, o chão/ The ground, in the palm of the hand, the ground, the ground

E manhã redonda de pedras altas/ And round morning of high crags

Cruzou fronteira da servidão / [He] Crossed the boundary of the beaten track

Olerê, quero ver / Olerê, I want to see

Olerê

E por maus caminhos de toda sorte/ And down bad paths of all sorts

Buscando a vida, encontrando a morte/ Seeking life, finding death

Pela meia rosa do quadrante Norte/ Down the half-rose of the North quadrant

João, João/ João, João

Um tal de Chico chamado Antônio/ A certain Chico named Antônio

Num cavalo baio que era um burro velho/ On a bay horse that was an old burro

Que na Barra Fria já cruzado o rio/ That on Cold Bar once you’re cross the river

Lá vinha Matias cujo o nome é Pedro/ Up came Matias whose name was Pedro

Aliás Horácio, vulgo Simão/ Actually Horácio, known as Simão

Lá um chamado Tião/ There one named Tião

Chamado João / Named João

Recebendo aviso entortou caminho/ Receiving warning, he zig-zagged his path

De Nor-Nordeste pra Norte-Norte/ From North-Northeast to North-North

Na meia vida de adiadas mortes/ Down the half life of delayed deaths

Um estranho chamado João/ A stranger named João

No clarão das águas/ In the brightness of the waters

No deserto negro/ In the black desert

A perder mais nada/ To lose nothing more

Corajoso medo/ Courageous fear

Lá quero ver você/ I want to see you there

Por sete caminhos de setenta sortes/ Down seven paths of seventy fortunes

Setecentas vidas e sete mil mortes/ Seven-hundred lives and seven-thousand deaths

Esse um, João, João/ That one, João, João

E deu dia claro/ And the day came bright

E deu noite escura/ And the night came dark

E deu meia-noite no coração/ And midnight came to the heart

Olerê, quero ver/ Olerê, I want to see

Olerê/ Olerê

Passa Sete-Serras/ He passes Sete-Serras (Seven Ranges)

Passa Cana-Brava/ Passes Cana-Brava (Wild Cane)

No Brejo das-Almas/ In the Swamp-of-Souls

Tudo terminava/ Everything ended

No caminho velho onde a lama trava/ On the old trail where the mud traps

Lá no Todo-fim-é-bom/ There at the ‘Every-end-is-good’*

Se acabou João/ João came to his end

No Jardim das rosas / In the garden of roses

De sonho e medo / Of dream and dread

No clarão das águas / In the brightness of the waters

No deserto negro / In the black desert

Lá, quero ver você / There, I want to see you

Lerê, lará / Lerê, lará

Você me pegar/ You catch me

— Commentary —

Guimarães Rosa está dentro da minha obra…/ [G.R.] is woven into my workTentava ler Grande Sertão/ I tried to read Grande Sertão… e não consegui/ and I couldn’tporque era denso, pesado / because it was dense, challengingDepois, aquilo virou uma sopa no mel / Later, it became like ‘bread with honey’Aquilo virou a minha casa!/ It became my home!– Tom Jobim

I started this post nearly two years ago. At the time, to try to better understand the song, I read Guimarães Rosa’s Sagarana (1946), a compilation of nine novellas, including the one that inspired this song, Duelo.

When a friend in Rio heard what I was doing, he said, “Tory, escolhe outra música” — choose another song.

João Guimarães Rosa (1908-1967) is one of those authors who’s notoriously difficult to understand even for Brazilians: a modernist known for his neologisms and resurrection of obsolete regional dialect (his work has been compared to James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake), he’s an even greater challenge for non-native speakers, and pretty near impossible to translate. At writing, there’s still no good English translation of his 1956 master work, Grande Sertão: Veredas.

But his writing was also of particular inspiration to Brazilian composers: His literary alchemy reproduced in print the soundscape of the sertão — a soundscape that his protagonist in Grande Sertão: Veredas calls “muito cantável” — very singable. Rosa’s prose itself has a unique sonority. In a 1964 letter to his English translator (cited here), he said his text carried an “underlying music,” something he crafted through those same techniques that make his work a challenge to understand.

All of that was attractive to Brazilian composers wishing to capture the essence of their county in song. Brazilian historian Heloísa Starling (from Rosa’s state of Minas Gerais) has said that Rosa “may be the Brazilian writer whose poetic language has had the deepest influence on Brazilian popular song.”

“Matita Perê” is one of the songs in Tom Jobim’s and Paulo César Pinheiro’s repertoires that reveals the clearest connections to Rosa’s work, while also incorporating literary references to Carlos Drummond de Andrade’s 1967 poem “Um chamado João” (itself a tribute to João Guimarães Rosa, published three days after his death) and Mário Palmério’s 1965 novel Chapadão do Bugre (referenced in the verse beginning “Lá vinha Matias cujo nome é Pedro…”) All three authors were from Minas Gerais, a vast state approximately the size of Texas whose wild landscapes and backland hamlets provided the setting for Rosa’s fiction.

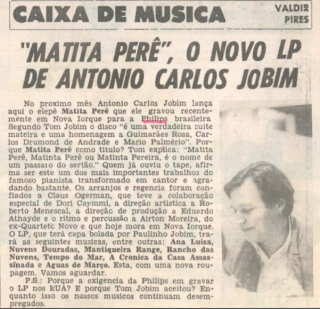

The song is the title track of Tom Jobim’s first independently produced album, released in 1973. The album represented a watershed in Jobim’s career: It marked his shift away from bossa nova and its Rio-centrism, as the deep connections to Minas Gerais here reveal. This is the beginning of Tom’s “mato” (woods) period — where his work increasingly canonized Brazil’s incredibly diverse flora, fauna and folklore, accompanied by deeper experimentation with harmony and orchestration. As Jobim put it in a comment cited in Cancioneiro Jobim, “Our work of musical creation is a very Brazilian thing, ever and always. I really feel Brazil, the earth, our animals. We pick up a little branch here, a little leaf there, a colorful seed up ahead, a parrot, a jandaia frog, and we put those things together, until they become ‘Águas de março,’ ‘Matita Perê,’ ‘Boto,’ all based on the Brazilian forest, the sertão, on the fish and birds of Brazil.”

Tom seemed ready for that change– and the challenge it represented — after his bossa nova period: “It’s tough to figure out how to put on paper things that are in our souls,” he said of Matita Perê. “How to speak, for example, of Matita Perê? I’m writing lyrics, something I’d never done with such dedication. I wrote lyrics before, sure, but talking about Corcovado, etc. Matita speaks a different language, it’s not a romantic song, there’s no love, no woman.”

As Tom mentions, with this album, he began writing more of his lyrics himself — including parts of the lyrics for “Matita Perê.” For this song, once he had some fragments down, he sought out his friend and renowned lyricist Paulo César Pinheiro.

Pinheiro has similarly drawn great inspiration from Guimarães Rosa throughout his career: He recalls having read all of Rosa’s work as a teen, enraptured. In 1968, Pinheiro composed “Sagarana (A Tribute to João Guimarães Rosa)” with João de Aquino, and entered it into the 1969 IV Festival Internacional da Canção. As Pinheiro writes, Jobim called him a few days later telling him he’d heard and loved “Sagarana” and needed to talk about an idea he had. Jobim showed Pinheiro the music and the lyrics he’d composed so far to give him an idea of the thrust of the song — of the dramatic flight. Pinheiro took on the rest. It was harder than he’d expected, he says, in part because of the puzzle of fitting verses around those Tom had already written. He adjusted certain parts of the melody to fit the story as he developed it, and once he was finally satisfied, says he called Tom in euphoria and dictated “over the telephone what would become, from that moment on, our ‘Matita-Perê.'”

On the inspiration for “Matita Perê,” Tom told Dori Caymmi, who helped with some of the arrangements for the album, “tudo começo com o pio de um passarinho” — it all started with a bird’s call: presumably the matita pereira bird.

The bird, a striped cuckoo, is attributed mystical qualities in Brazil’s backlands (sertão). Its song — two notes, rising a half-tone, cited in the song to indicate impending danger (hear, for instance, min. 2:16-2:21 and 4 to 4:06) — is, according to regional superstition, the voice of destiny and of the mysteries of the deep bush. That occult reputation is due in part to the bird’s elusiveness: it sings into tree trunks, its song bouncing and echoing in paths impossible to trace.

The bird is not only considered an augur, but also a witch of sorts; if its song is heard at night, it means the witch is requesting tobacco from the household that hears it, as renowned Brazilian folklorist Luís da Câmara Cascudo described in his dictionary of Brazilian folclore:

Matintapereira: Mati, mati-taperê: name of a diminutive owl, which is considered an augur. When, in the dead hours of the night, people hear the mati-taperê sing, anyone who hears it and is at home says: Matinta, tomorrow you can come for tobacco. […] Hard luck for whoever is the first person to arrive at that house the next day, because they’ll be considered the mati. That’s because, according to indigenous belief, witches and shamans turn into the bird to travel from one place to another to take vengeance…. The Matintapereira is also a form of the myth of saci-pererê in his ornithomorphic form.

As Cascudo mentions, Matintapereira, or Matita Perê, is also one of the names of the Brazilian trickster figure Sací, who I wrote about here.

The album Matita Perê also includes “Águas de março,” which Tom composed while taking a break from the epic “Matita Perê.” “Águas de março” actually mentions the bird in its lyrics (“Caingá candeia, é o matita-pereira”), which are similarly based on literature — in this case Olavo Bilac’s poem “O Caçador de Esmeraldas.”

As you may have noticed, the song’s verses are irregular, prioritizing dramatic story-telling over poetic structure. Like Guimarães Rosa’s novellas, the story and accompanying music build tension toward a tragic ending. In Rosa’s novellas, the ending is usually not what the reader expected — but no less tragic: Duelo tells the story of two enemies scheming to finish each other off; the mortal rivalry would appear to end with the death of one of the protagonists from illness. But the dead man passes his hatred onto an heir, and, from the afterlife, chases down and kills his rival.

In the song, the chase, real dreams and delayed death, and the tragic ending are all allusions to that story. The language in the song also mimics Rosa’s literary techniques: In a recent conversation, Pinheiro explained to me that he invented the phrase *“Manhã noiteira de força-viagem,” for instance, in the same way Guimarães crafted new phrases to reflect and pay tribute to the dialect of the backcountry. “Manhã noiteira” — translated here as “Nightish dawn” — refers, as you can perhaps infer, to the earliest hours of daybreak; “of journey-force” is meant to imply that the day broke driving a forced journey — the protagonist’s flight. *“Todo-Fim-é-Bom” — Every-End-is-Good — and Sete-Serras are place names taken from Sagarana; I think Cana-Brava appears in Grande Sertão: Veredas. Rosa said he wrote Sagarana in seven months, then rested for seven years; as in this song, the number seven takes on a special significance in his stories, surely for its superstitious symbolism as well as its sonority.

The harmony of the song meanwhile zig-zags like the protagonist’s flight route, while the rhythm and orchestration stir a sense of foreboding.

Tom was inspired to write the song when he was immersed in nature at his mountain retreat in Poço Fundo, RJ. He began recording the album at CBS Studios in downtown Rio de Janeiro, but after recording “Matita Perê,” he wasn’t satisfied with the results, and decided to go to New York and start over. According to Tom’s son, Paulo Jobim (in Cancioneiro Jobim: Obras Completas vol. IV) Jobim placed more confidence in New York’s studios and session musicians; the session musicians for this album included string players from the New York Philharmonic Orchestra.

Dori Caymmi said that Tom arranged the music and Claus Ogerman took care of instrumentation. (For those interested in more nitty-gritty details: Caymmi has said that Ogerman added five measures, 90 through 94, with a section of flutes and double-bass that give the sense of a horse’s gallop and chase.)

Main sources for this post: “A singular sonoridade de Matita Perê construída por meio da parceria de Tom Jobim e Claus Ogerman” (here) by Patrícia de Almeida Ferreira Lopes (2017); Cancioneiro Jobim: Obras Completas; “Tom & Rosa” by Heloísa Starling (2010); Histórias de Canções: Tom Jobim, by Wagner Homem and Luiz Roberto Oliveira; Paulo César Pinheiro’s Historias das Minhas Canções; and very helpful input from Paulo Jobim and Paulo César Pinheiro!

What a wonderful post, Ms. Broadus! I bought the LP (long since replaced with the CD version) back in the mid-70s from a record store in DC that had a knack (perhaps with some advice from Felix Grant?) of knowing which Brazilian records to import, but I never knew about the literary inspiration for the title song (which, I confess, is a bit over my head). For that matter, I had never tried to look for a translation of the lyrics (much less attempted one on my own). Your observation about this album being a turning point for Jobim is so true, yet never had occurred to me. And your backstories on the recording process were fascinating, too. Muito obrigado!

Obrigada, Richard! Thanks so much, I really appreciate it!

What a marvelous explanation of the meaning and history of Matita Perê! I think that I encouraged you to write about this amazing song several years ago. So glad that you did. I like the performance by Milton Nascimento the best.

Thanks so much! Yes, I remember I’d started it because of a request (and then even more requests for the song rolled in) but then left it aside for a couple years. So glad you liked it, thanks for the comment.

Excelente pesquisa e muito obrigado pelo texto! Acabei de ler Sagarana e fiquei maravilhado com os paralelos traçados por Tom e Paulo César Pinheiro em “Matita-Perê”. Essa sempre foi uma das minhas canções favoritas do Tom, cuja letra tão bonita e misteriosa sempre me intrigou muito. Aliás, a fase do Tom “mateiro” é realmente a minha favorita 🙂

Obrigada, Virgilino!!!

Dear Victoria: I subscribe to your ‘Lyrical Brazil.’ I am deeply in love with Tom Jobim and with Matita Perê (and with Brazilian music in general). As a subscriber, I’ve had this since you posted it, but I’ve only gotten around now, more than a year later, to absorbing your highly illuminating translation and commentary. I can’t tell you how much I appreciate that you do ‘Lyrical Brazil’ for the love of it and from a desire to share what you love — and so thoroughly research and wonderfully write about (you are a very good writer) — with the rest of the world. Muito obrigado!

Thank you so much for taking the time to write this, Randy, I really, really appreciate it! – Victoria