Lyrics from “Sabiá” (Song-Thrush), 1968

Music by Tom Jobim

Lyrics by Chico Buarque

—

I’m going to go back

I know that I’m going to go back, yet

To my place

It was over there

And it’s still over there

And I will hear

Singing

A Sabiá

Singing

A Sabiá

I’m going to go back

I know that I’m going to go back yet

I’m going to lie down

In the shade of a palm tree

That’s no longer there

Pick the flower

That no longer blooms

And some love

Perhaps might frighten away

The nights that I don’t wish for

And announce the day

I am going to go back

I know that I’m going to go back, yet

It won’t be in vain

That I made so many plans

Of fooling myself

How I made delusions

Of finding myself

How I made roads

For losing myself

I did everything and nothing

For forgetting you…

I’m going to go back

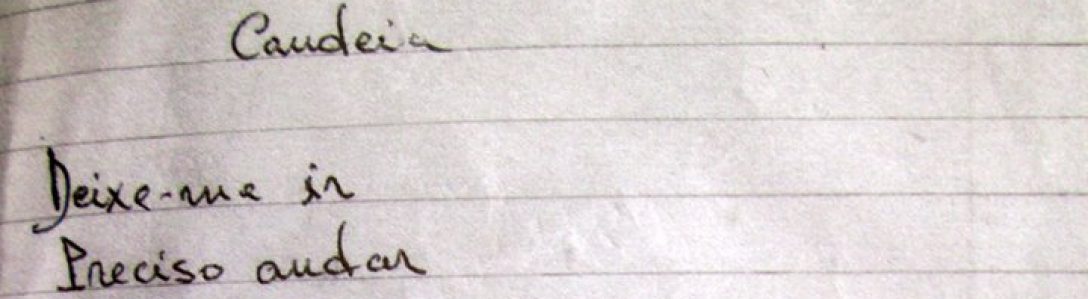

Forgotten verse: added by Tom Jobim and rejected by Chico Buarque (and dropped by Tom Jobim):

I’m going to go back

I know I’m going to go back yet

And it will be for good

I know love exists

I’m not sad anymore

And the new life is about to arrive

And this lonesomeness is going to end

And this lonesomeness is going to end

— Interpretation —

“Sabiá” was the winner of Brazil’s 1968 III International Festival of the Song. The victory caused outcry among fans of a competing song, Geraldo Vandré‘s more explicitly rebellious anthem – a call to arms against the military regime – “Pra não dizer que não falei das flores (Caminhando).” Critics claimed “Sabiá” was “escapist” in comparison with Vandré’s wildly popular song, which came in second place. But a closer look shows that the lyrics evoke a sense of nostalgia for a lost Brazil that was a direct blow to the oppressive military regime that had taken power in 1964, and much of the criticism can be blamed on a final verse that was added at the last minute by Tom Jobim and dropped quickly thereafter.

Sabiá can be classified as a “song of exile,” evoking symbols and imagery from the most well-known song of exile, the poem”Cánção do Exílio,” 1843, by Gonçalves Dias. Gonçalves Dias’s poem, which he wrote while studying at University of Coimbra, in Portugal, came to represent an archetype of an optimistic, romanticized song of exile; in turn, songs like Sabiá serve as a parody, contrasting the romanticized Brazil from the mid-19th century with the dismal reality under military rule. In Sabiá, the exile from Brazil is temporal, rather than geographical. (Incidentally, shortly after the 1968 festival, both Chico Buarque and Geraldo Vandré went into exile.)

Dias longs for Brazil’s abundant palm trees and flowers, which in “Sabiá” are “no longer there.” Dias says “Lonely night-time meditations please me more when I am there”; in “Sabiá,” however, the narrator doesn’t want these nights – which now represent oppression – to come. Even the love or lover, taken for granted in Dias’s poem, becomes something uncertain in “Sabiá.”

Still, while in “Canção de Exilio” Dias pleads to God to return to Brazil before dying, the poet in “Sabiá” makes a firmer declaration, stating “I am going to go back, I know.”

Here is a full English translation of Canção do Exilio. The elements of Brazil that Dias speaks of – the Sabiá (Rufous-Bellied Thrush), palm trees, flowers, loves, and the idea of “over there” – appear again and again in Brazilian popular music. (Gilbert Gil, for example, alludes to Dias’s poem in his exile song “Back in Bahia.”)

Sabiá was one of the first songs Chico Buarque and Tom Jobim composed together. (The first was “Retrato em Branco e Preto“/Portrait in Black and White, from 1967). During these early days of their partnership — which continued until Tom’s death, in 1994 — Chico admits there was still a certain distance between the two. Chico revered Tom, and Tom treated Chico a bit more like a pupil than a partner, responding to his lyrics with effusive praise and encouragement.

Later on, as the two became more comfortable working together, they would admittedly argue heatedly over each word that went into the songs they wrote together. Still, Tom’s desire to control the lyrics in his songs already manifested itself in Sabiá: After the two finished the song, Chico went on a trip, and in his absence, Tom added the final verse – in gray, above – because he thought the song was repetitive and needed additional lyrics. Chico confesses he was a bit peeved when he found out about the change. At any rate, he says, Tom came around and quickly abandoned the final verse, which had changed the tone of the song and invited sharp criticism of the song as escapist.

Sources for this post: Luiz Roberto Oliveira’s interviews with Chico Buarque, on Tom Jobim’s website, and Adélia Bezerra de Meneses’s book Desenho Mágico: poesia e política em Chico Buarque (Editora Hucitec, São Paulo, 1982).

Post by Victoria Broadus

Thank you for this perceptive explication of the song “Sabia,” one of my favorites as I discover the musical treasury of Brasil. As someone pointed out, Tom Jobim’s opening few bars actually mimic the sabia’s song. Such a magical time, this musical era in Brasil!

Yes, thank you Fred!